- Introduction: The Paradox of Plenty and Scarcity

India, a nation with over 1.4 billion people, finds itself at the brink of an escalating water crisis, presenting a stark paradox of both water-richness and severe scarcity. Despite receiving substantial monsoonal rainfall annually, large parts of the country are grappling with profound water stress. This stress manifests in various critical ways, including parched farmlands, empty taps in urban centers, and widespread contamination of existing water sources. While natural factors such as uneven rainfall distribution do play a role, a critical examination of the situation overwhelmingly reveals that the root causes of this crisis are predominantly man-made. Years of mismanagement, excessive over-extraction of water resources, rampant pollution, and significant policy failures have collectively converged to create what can only be described as a perfect storm, threatening the nation’s health, economy, and social stability. Understanding the intricate and multifaceted roots of this crisis is paramount for effectively shaping sustainable and long-term solutions.

- The Current Water Landscape in India: A Precarious Balance

India is home to approximately 18% of the global population, yet it has access to only about 4% of the world’s freshwater resources. This profound imbalance, compounded by pervasive mismanagement, has led to a dire situation across the country. According to a NITI Aayog report, nearly 600 million people in India experience high to extreme water stress. The human cost of this crisis is devastating, with over 200,000 individuals dying annually due to inadequate access to safe water. Projections indicate an alarming future: by 2030, the country’s water demand could double the available supply, a scenario that has the potential to displace hundreds of millions of people and severely jeopardize economic growth across the nation.

Groundwater is the backbone of India’s water security, playing a crucial and often understated role in supporting both agricultural and domestic needs. It accounts for nearly 60% of irrigation and a staggering 85% of drinking water across the country. However, this vital resource is under immense and unsustainable pressure. India holds the dubious distinction of being the world’s largest extractor of groundwater, extracting more than the USA and China combined. This unchecked extraction has led to alarming declines in water tables in several states, including Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu, as well as parts of eastern India.

Despite receiving substantial annual average precipitation of around 4,000 cubic kilometers, with approximately 3,000 cubic kilometers falling during the crucial monsoon season, India faces significant challenges in effective water utilization. A staggering amount, roughly 2,131 cubic kilometers of monsoon water, is lost due to evaporation and soil absorption, highlighting a critical deficit in effective storage, conservation, and equitable distribution mechanisms. Only a small fraction of the available water is effectively utilized or recharged into aquifers. The Central Water Commission itself acknowledges that India possesses sufficient water resources, yet water stress persists and is escalating. This points to systemic issues where fragmented planning, inadequate infrastructure, and poor governance prevent efficient harnessing and distribution, leading to localized scarcity even in regions that are considered water-rich.

- Key Drivers of the Man-Made Crisis

The deepening water crisis in India is overwhelmingly a consequence of human choices, systemic failures, and deeply ingrained practices.

3.1. Unsustainable Agricultural Practices: The Thirsty Giant

Agriculture is the single largest consumer of freshwater in India, accounting for a massive 80-90% of total usage. This sector, while vital for food security, has ironically become a primary driver of the water crisis due to deeply ingrained unsustainable practices:

- Water-Intensive Crop Choices: Government incentives, such as Minimum Support Prices (MSP), have historically encouraged the cultivation of water-guzzling crops like rice (paddy) and sugarcane. This encouragement extends even to agro-climatically unsuitable and arid regions. For instance, producing a single kilogram of rice can require approximately 3,500 liters of water. States like Punjab and Haryana, despite being semi-arid, are major rice producers heavily reliant on intensive groundwater pumping. The relentless focus on a few staple, water-intensive crops has severely hindered the adoption of more resilient and less water-demanding alternatives that would be suitable for local conditions, further reducing agricultural resilience to climate variability.

- Inefficient Irrigation Methods: The widespread prevalence of flood irrigation is a major contributor to water wastage. This method, where entire fields are inundated, leads to significant water loss through evaporation, runoff, and deep percolation beyond the root zone. Despite their proven efficiency, micro-irrigation techniques like drip and sprinkler systems have seen very limited adoption across the country.

- Electricity and Water Subsidies: The provision of subsidized or free electricity for agricultural pumps is a critical factor accelerating groundwater depletion. These subsidies incentivize indiscriminate pumping by farmers, effectively removing any economic disincentive for excessive water use, even as groundwater levels plummet.

3.2. Industrial and Urban Pollution: Contaminating the Source

Rapid industrialization and urbanization have fundamentally transformed India’s water bodies into toxic dumping grounds, drastically reducing the availability of potable water.

- Industrial Effluents: Many industries, particularly those in sectors like textiles, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and thermal power plants, discharge untreated or inadequately treated wastewater directly into rivers, lakes, and even groundwater. This effluent is frequently laden with heavy metals (such as chromium, lead, and mercury), toxic chemicals, and various organic pollutants, rendering the water completely unfit for any use. Industrial clusters along major rivers like the Ganga and Yamuna are notoriously high for their pollution levels.

- Urban Sewage: India’s rapidly expanding urban centers often lack adequate sewage collection and treatment infrastructure. A significant portion of municipal wastewater flows untreated into natural water bodies. This introduces pathogens, excessive nutrients, and organic matter, leading to environmental problems like eutrophication, oxygen depletion, and a host of waterborne diseases. For example, only about 30% of India’s sewage is treated, with the remainder polluting surface water bodies.

- Chemical Runoff: Agricultural runoff, containing residual pesticides, herbicides, and excessive fertilizers, seeps into groundwater and flows into surface water bodies. This contributes significantly to both chemical pollution and nutrient loading in the water systems.

- Solid Waste Contamination: Improper disposal of solid waste, particularly plastic waste, not only clogs waterways but also leaches harmful chemicals into the soil and water, severely compromising water quality. The cumulative effect of these pollution sources is a drastic reduction in the quality and quantity of usable water, posing severe health risks to communities reliant on these contaminated sources.

3.3. Flawed Water Governance and Policy

A significant and pervasive contributor to India’s water crisis is the deep-seated lack of coherent and integrated water governance. The institutional framework for water management is often fragmented, leading to widespread inefficiencies, duplication of efforts, and a profound lack of accountability.

- Fragmented Institutions and Overlapping Jurisdictions: Water management responsibilities are frequently distributed among multiple ministries, departments, and agencies at central, state, and local levels. This leads to poor coordination, conflicting priorities, and a lack of holistic planning. This ‘siloed’ approach fundamentally prevents integrated river basin management and comprehensive water resource planning. Water being a state subject further exacerbates fragmented governance and inter-state disputes.

- Weak Enforcement and Regulatory Gaps: Despite the existence of numerous environmental and water laws, their enforcement is often weak. This weakness is attributable to factors such as limited capacity, corruption, and political interference. Regulatory bodies frequently lack the mandate, sufficient resources, or political will to hold polluters accountable or to curb unsustainable practices effectively.

- Data Deficiencies and Lack of Transparency: Reliable and up-to-date data on water availability, demand, usage, and quality is often scarce or inaccessible. This significant deficiency hinders evidence-based policy formulation and effective monitoring of water resources. A lack of transparency in water resource allocation further exacerbates issues of equity and efficiency.

- Inadequate Community Participation: Traditional, often community-driven, water management systems have regrettably eroded over time. Modern governance structures frequently overlook the crucial role that local communities can play in water conservation, management, and conflict resolution. This results in top-down approaches that may not be locally appropriate or sustainable. Traditional water management systems like baolis, tanks, and johads have been disregarded and replaced by urban construction. Thousands of lakes, ponds, and wetlands have vanished due to encroachment and real estate development; for example, Ahmedabad lost 37 of its 172 lakes in recent decades.

- Policy Implementation Gaps: While policies exist (such as the National Water Policies, with the latest dating from 2012 and ongoing revisions), the gap between policy intent and ground-level implementation remains substantial. Ambitious schemes often face delays, insufficient funding, or poor execution. For instance, the progress of State Water Action Plans under AMRUT 2.0 has been noted as slow in many states.

3.4. Groundwater Depletion: The Silent Crisis

India is the world’s largest extractor of groundwater, accounting for approximately 25% of global groundwater withdrawals. This means India pumps out more groundwater than the USA and China combined. This silent crisis is driven by several critical factors:

- Unregulated Extraction: The widespread availability of borewells and submersible pumps, coupled with a pervasive lack of stringent regulations, has led to unchecked groundwater extraction across the country. In many regions, particularly in the agricultural belts of Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and parts of the Deccan Plateau, groundwater extraction far exceeds the natural recharge rate. Even with some recent improvements, as of 2024, 11.13% of assessment units are still categorized as “over-exploited”. While this figure is down from 17.24% in 2017, the sheer volume of extraction remains concerning, with 90% of it going to irrigation. In some areas, borewells now reach depths of 400 to 600 feet.

- Energy Subsidies: As previously highlighted, heavily subsidized or free electricity for agricultural pumps directly fuels the over-extraction of groundwater, making it economically viable for farmers to irrigate water-intensive crops even when groundwater levels are plummeting.

- Consequences of Depletion: The consequences of this rampant groundwater depletion are dire and far-reaching:

- Falling Water Tables: Groundwater levels are continuously dropping, necessitating deeper and more expensive borewells, which are often beyond the financial reach of small and marginal farmers. In some areas like Punjab, water tables are falling by nearly a meter annually.

- Increased Pumping Costs: Deeper pumping directly increases energy consumption and operational costs for farmers, adding to their financial burden.

- Land Subsidence: In certain areas, rapid groundwater withdrawal leads to the compaction of aquifers and the subsequent sinking of land, which can cause significant damage to infrastructure.

- Saltwater Intrusion: In coastal regions, over-pumping of freshwater aquifers allows saline seawater to intrude, rendering the groundwater unfit for both consumption and agriculture. Gujarat, for example, faces significant groundwater contamination due to salinity in 28 out of its 33 districts.

- Contamination: Lower water tables can also increase the concentration of natural contaminants such as arsenic and fluoride. Moreover, reduced water levels allow surface pollutants to seep more easily into aquifers. Approximately 56% of India’s districts have groundwater with nitrates beyond safe limits.

3.5. Climate Change as an Amplifier (Man-Made Climate Change)

Anthropogenic climate change, driven by global greenhouse gas emissions, significantly amplifies India’s existing water crisis. While some climate variability is natural, the human-induced component is undeniably making the crisis more acute and harder to address.

- Altered Rainfall Patterns: Climate change is leading to more erratic and unpredictable monsoon patterns. This includes fewer rainy days but more intense rainfall events, which simultaneously increase flood risks in some areas while prolonging dry spells and droughts in others. This heightened variability makes water planning and management exceedingly difficult.

- Glacier Melt: The Himalayan glaciers, which serve as crucial water sources for major perennial rivers like the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra, are melting at an accelerated rate due to rising temperatures. While this initially leads to increased river flows, the long-term prognosis is a significant reduction in water availability as glaciers retreat, threatening the water security of millions. The World Bank estimates a potential 20% decrease in the Ganges basin flow by 2050 due to glacier shrinkage.

- Increased Evaporation: Higher ambient temperatures, a direct consequence of global warming, lead to increased evaporation rates from surface water bodies (reservoirs, lakes, rivers) and soil moisture. This reduces the effective water available for consumption and agriculture, particularly during dry seasons.

- Extreme Weather Events: The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like heatwaves, droughts, and floods are demonstrably increasing. These events disrupt the natural hydrological cycle, placing immense stress on water infrastructure, damaging agricultural yields, and negatively impacting water quality.

- Social and Economic Ramifications

The man-made water crisis in India has profound and far-reaching social, economic, and environmental consequences.

4.1. Health Impacts

Contaminated water sources directly lead to a high incidence of waterborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal illnesses. These diseases disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, placing an enormous burden on public health systems and resulting in significant lost productivity. The World Bank estimates that nearly 21% of communicable diseases in India are related to unsafe water. Poor sanitation further exacerbates this health burden, especially for children and marginalized communities.

4.2. Economic Losses

- Agriculture: Reduced water availability directly leads to crop failures, lower yields, and increased input costs for farmers (e.g., for deeper borewells and higher pumping costs). This pushes farmers into crippling debt, leading to widespread rural distress and, in severe cases, farmer suicides. Paradoxically, even during floods, water may not be available for irrigation due to poor storage infrastructure. India’s inefficient water use in agriculture also means it is “virtually exporting” billions of liters of water through the export of water-intensive crops.

- Industry: Water scarcity and pervasive pollution directly affect industrial operations, leading to production cuts, higher water treatment costs, and ultimately hindering overall economic growth. Many thermal power plants, which are heavily reliant on water for cooling, are located in water-stressed regions, leading to operational challenges.

- GDP Impact: The NITI Aayog report in 2019 issued a stark warning that India could face a potential 6% loss of its GDP by 2050 due to the escalating water crisis.

4.3. Migration and Conflict

Water scarcity often forces internal migration from rural to urban areas, placing additional pressure on already strained urban infrastructure. It can also ignite inter-state and inter-community conflicts over shared water resources, as seen in ongoing disputes over river waters.

4.4. Vulnerable Communities

The poor and marginalized sections of society, particularly women and children, are disproportionately affected by the water crisis. Women often bear the primary burden of walking long distances to fetch water, which significantly impacts their education, health, and economic opportunities. Access to safe and affordable water becomes a significant financial burden for low-income households, who often end up paying more for water than affluent households. In cities, water access is highly unequal; while affluent neighborhoods may have regular piped water, slums and informal settlements often depend on expensive tankers or unreliable hand pumps. This disparity not only reflects existing class inequities but also fuels social unrest.

4.5. Ecological Degradation

Crucial ecosystems such as wetlands, rivers, and groundwater-dependent ecosystems are rapidly degrading across India. The disappearance of these vital systems threatens biodiversity and the essential services they provide, such as flood mitigation and groundwater recharge. Climate change further amplifies these effects through erratic rainfall and rising temperatures.

- Government Responses and Limitations

Several government initiatives have been launched to address India’s complex water crisis, demonstrating a commitment to change. However, these initiatives often face significant limitations in their implementation and overall impact.

- Jal Jeevan Mission: Launched in 2019, this flagship scheme aims to provide functional tap water connections to all rural households by 2024. As of mid-2025, significant progress has been reported in certain states. However, persistent challenges remain, particularly concerning water source sustainability and ensuring the quality of the water supplied.

- Atal Bhujal Yojana: This scheme specifically encourages community participation in groundwater management in over 8,000 gram panchayats. Despite its laudable goals, its impact is limited by factors such as slow implementation and a persistent lack of technical capacity at the grassroots level.

- Namami Gange Programme: Intended to rejuvenate the sacred river Ganga, this project has yielded mixed results. While there have been improvements in sewage treatment capacities, persistent pollution and encroachments continue to remain major hurdles, preventing the full realization of the program’s objectives.

- Towards Sustainable Solutions: A Man-Made Path Forward

Recognizing the undeniable man-made nature of India’s water crisis implies a crucial truth: the solutions must also be man-made, necessitating a concerted, multi-pronged approach.

6.1. Policy Reforms and Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM)

A fundamental shift in policy and governance is required to manage water holistically.

- Holistic Planning: Implement Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) that considers water as a single, interconnected system, encompassing surface water, groundwater, and rainfall, across entire river basins. This necessitates better coordination among various government agencies and states. India needs a unified national framework that brings together groundwater, surface water, and rainfall under one comprehensive plan, requiring institutional restructuring and inter-departmental coordination.

- Rationalizing Subsidies: Gradually reform electricity and water subsidies in agriculture to incentivize efficient water use. This could be achieved through mechanisms such as direct benefit transfers or smart metering. The overuse of subsidized water for water-intensive crops like paddy must be curtailed.

- Strengthening Regulatory Frameworks: Enact and rigorously enforce laws for groundwater regulation, industrial effluent discharge, and urban sewage treatment. This requires establishing independent regulatory bodies with sufficient powers, resources, and political will to ensure accountability. Water rights must be legally recognized.

- Water Pricing and Auditing: Introduce realistic pricing for water use across all sectors to encourage conservation and generate essential funds for infrastructure maintenance. Furthermore, mandate water audits for industries and large urban consumers to monitor and control their water consumption.

6.2. Technological Interventions and Infrastructure Development

Investing in smart and sustainable technologies and infrastructure is crucial for efficient water management.

- Efficient Irrigation: Promote the widespread adoption of micro-irrigation technologies like drip and sprinkler systems through various means, including subsidies, extensive awareness campaigns, and technical support to farmers.

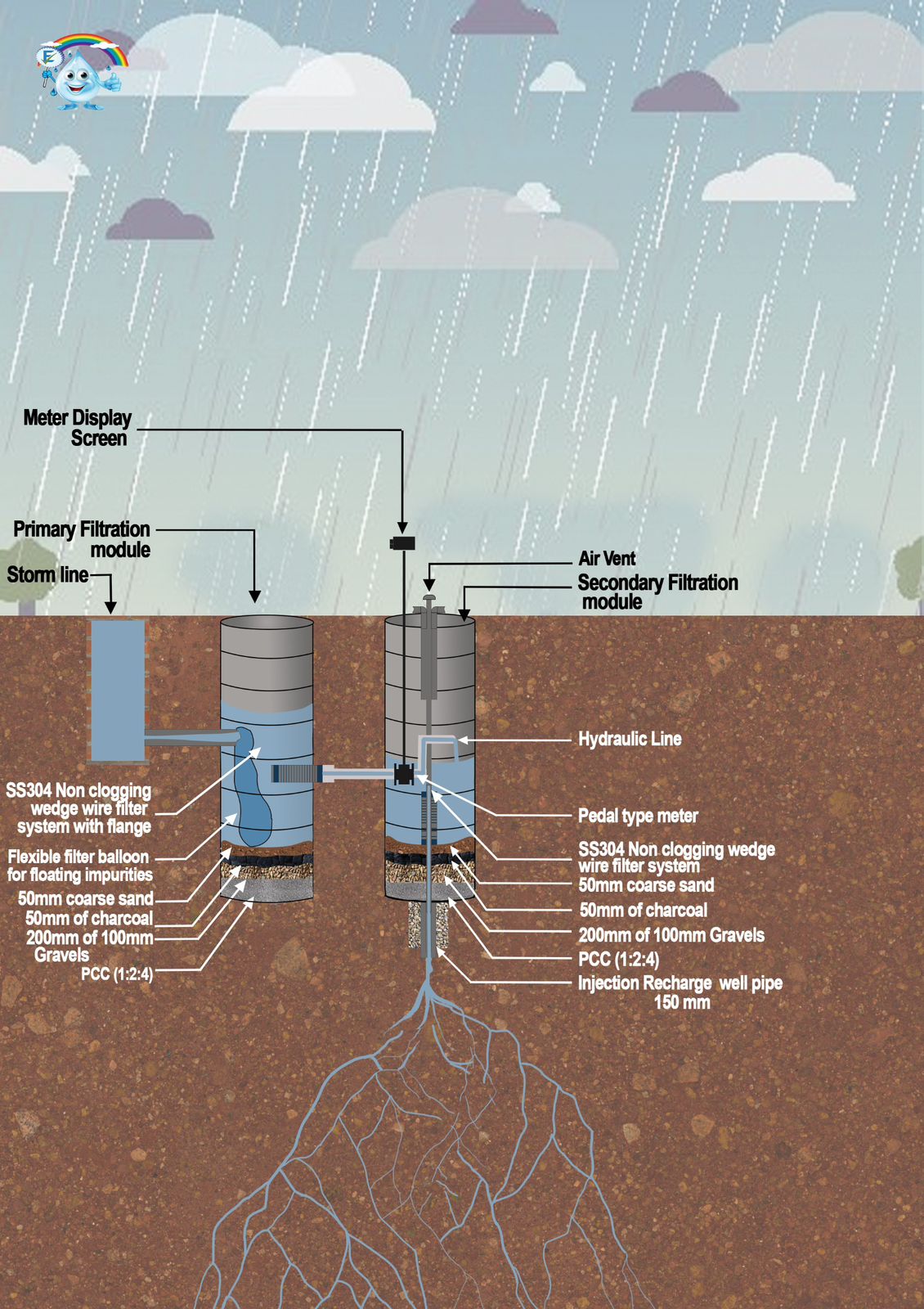

- Rainwater Harvesting: Implement rainwater harvesting structures at household, community, and larger scales. This includes rooftop harvesting in urban areas and the revival of traditional structures like johads, ponds, and check dams in rural regions to recharge groundwater and provide local water sources. Initiatives such as Jal Shakti Abhiyan and Mission Amrit Sarovar aim to bolster these efforts.

- Wastewater Treatment and Reuse: Invest heavily in building and upgrading sewage treatment plants (STPs) and industrial effluent treatment plants (ETPs). Crucially, promote the reuse of treated wastewater for non-potable purposes, such as industrial cooling, irrigation, and gardening, thereby reducing demand on fresh water resources.

- Smart Water Management: Pilot and scale up technologies like IoT-enabled meters, AI-based leak detection, and GIS mapping to significantly reduce water loss and effectively monitor water distribution. These tools, though nascent, hold significant promise for scaling efficient water management.

- Desalination and Advanced Treatment: Explore the feasibility of desalination plants for coastal areas and advanced treatment technologies for brackish water where they are economically viable.

6.3. Community Participation and Behavioral Change

Empowering local communities and fostering a culture of water conservation are foundational for long-term success.

- Empowering Local Bodies: Decentralize water governance and empower Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and urban local bodies to effectively manage local water resources with active community involvement.

- Awareness and Education: Launch widespread public awareness campaigns to foster a deep-seated culture of water conservation and responsible water use among citizens, industries, and farmers. Schools, media, and religious institutions can play a powerful and transformative role in promoting these conservation ethics.

- Reviving Traditional Practices: Support and revive traditional water harvesting structures and management practices, such as baolis, tanks, and johads. These systems are often exceptionally well-suited to local conditions and significantly promote community ownership. The work of organizations like Tarun Bharat Sangh in Rajasthan and Paani Foundation in Maharashtra are prime examples of successful community-led water revival and watershed development. These programs use community competitions to rejuvenate entire micro-watersheds, building local ownership and resilience.

6.4. Inter-State and International Cooperation

Addressing water challenges effectively often extends beyond state and national borders.

- River Basin Management: Foster greater cooperation between states sharing river basins to ensure equitable water allocation and collaborative management of shared resources.

- Transboundary Water Diplomacy: Engage in constructive dialogue with neighboring countries on transboundary river management to address shared water challenges effectively.

6.5. Water-Sensitive Urban Planning

Cities play a crucial role in water management and must adopt sustainable practices.

- Cities should adopt “sponge city” principles, emphasizing rainwater harvesting, permeable pavements, and green infrastructure.

- The restoration of urban lakes and catchments must be prioritized, as thousands of lakes, ponds, and wetlands have vanished due to encroachment and real estate development.

6.6. Data-Driven Decision Making

Accurate and accessible data is the bedrock of effective water governance.

- Investment in accurate and accessible data on water quality, quantity, and usage, along with hydrological monitoring and public transparency, is crucial for evidence-based policy formulation and effective monitoring.

- Conclusion: Turning Crisis into Opportunity

India’s water crisis is emphatically not an act of fate, but a direct consequence of decades of human choices and systemic failures. From the excessive pumping of groundwater for water-intensive crops to the unchecked discharge of pollutants into precious water bodies, and the fragmented governance that has failed to manage this critical resource holistically, the human footprint on this crisis is undeniable. While the challenges are immense and further exacerbated by the amplifying effects of human-induced climate change, the very fact that the crisis is largely man-made offers a crucial glimmer of hope: it can be resolved through collective human effort and decisive action.

A paradigm shift towards sustainable water management is not merely an option but an existential imperative for India. This shift must be characterized by integrated policy, innovative technological solutions, empowered communities, and responsible consumption patterns. Securing India’s water future demands an urgent, multi-stakeholder commitment to repair the damage done and build a truly water-secure nation for generations to come. The time to act is now; delay will only deepen the crisis, but timely intervention can transform this looming disaster into a profound story of resilience and renewal.